Menachem ben Qalonymus

Mythic Plausible - This post describes a fictional character who is partially based on a historical person Qalonymus ben Qalonymus, who was born in 1286. The historical Qalonymus was a member of the prominent Qalonymus family, translator of several works of mathematics and science from Arabic to Hebrew, and the author of a stirring poem that describes his desire to live a woman’s life in a woman’s body. The poem, as translated by Noam Sienna, is included below. It is worth a read as a reminder that ideas about gender have always been fluid, even 700 years ago. The fictional person is less of a scholar and seeks a magical way to change his gender.

The Provence Tribunal contains a thriving Jewish community that is independent from the rest of the Jewish world, though closely connected to the Jews of Spain, Rome, and Africa. They are Sephardic Jews, but with their own traditions. The Qalonymus family are the royalty of this part of the Jewish world, with the head of the family bearing the title of Nasi, or Prince. The family is involved with scholarship, naturally, but also with trade across the Jewish and gentile Mediterranean.

Menachem is a member of this family, though a junior one. He has spent some time in the beit midrash, but has not yet earned the title of hakham, or sage - a Sephardic term for rabbi. He is seen as a quiet and thoughtful young man, though one who is often distracted. He does not have a gift for Jewish study, though he is skilled with languages and has helped his family translate some texts and arrange business dealings with foreign merchants. The truth is that he is a deeply faithful man who is riven with feelings of confusion around gender.

In traditional Judaism men pray, as part of every morning service, “Blessed are you, O Lord, who has not made me a woman.” This prayer causes Menachem anguish every morning, because he does not want to thank Hashem for not being a woman. Indeed, he prays regularly that Hashem would make him a woman, as Hashem changed Dinah in Leah’s womb from male to female. So far his prayers have gone unanswered.

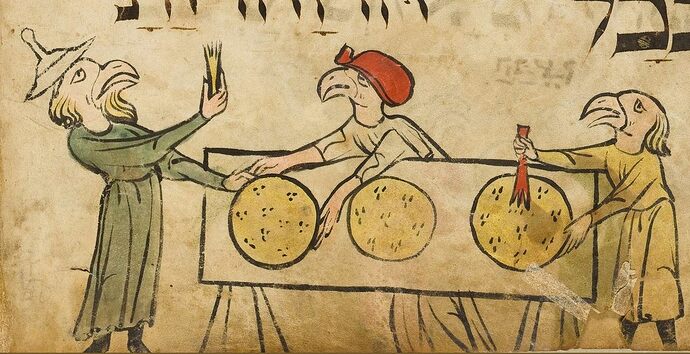

Menachem looks to his sisters and the other female members of his community and sees their lives as blessed. They do not labor under the heavy weight of the 613 commandments, as they are not subject to many of them. They work together with comradery, spinning thread and baking bread. They seem to have secret spaces and private whispered conversations that he wishes he could be a part of. At times he even wonders what it would be like to marry a man - to be provided for while at the same time being able to fulfill the quiet and intimate mitzvah of lighting the Shabbat candles (a traditional women’s observance).

Menachem’s prayers have not been answered, but he does not believe that his desires are against Hashem’s will. After all, Hashem created him with these desires. In reading Rambam he understands that miracles are part of the nature of the universe, and it is not right that a person should want a miracle to happen for him. Instead a person should understand that miracles will happen at the right time, in a way that seems natural. Rambam writes about the parting of the Red Sea and how a wind blew the water so that the sea parted. The wind was a miracle created at the beginning of time, waiting for that moment. In the same way, perhaps, Menachem decided that magic was a miracle that Hashem created that he had the right to seek out.

Menachem set out to find Hermetic Wizards and see if their magic can be used for miraculous purposes: to change him from a man to a woman. He succeeded, but not as he might have hoped. A Jerbition maga named Magdalene took Menachem in. She promised him that she could solve his problem, if he just did her a few favors.

The Jerbition was cursed with a Blatant Gift after a Twilight that went very badly. She needed a mundane agent who could manage her business interests and her connections with the larger merchant community of the Mediterranean. Menachem, with a broad command of languages, seemed a useful tool, especially since he could be strung along with the promise of giving him the transformation he craved.

Magdalene did create the item,a necklace, that Menachem needed, but she only gave it to him for a few hours at a time. She insisted that the necklace stay at the covenant so it would be safe, but also so that Menachem would always be beholden to her. She continuously made promises she did not keep, saying that the next task she had for him would be the last, and he would finally be given the necklace for good. But there was always just one more thing to do.

Eventually Menachem took matters into his own hands, reasoning that he had paid his debt to her a dozen times over. She knew that the necklace was what he wanted, so that was well guarded. But her library was another matter. He stole the text that described how the necklace was made, and a number of other books for good measure. With this stolen bounty, he reasoned, he might be able to make a more balanced deal at a different covenant.

Story Seed - The Thief’s Refuge

Menachem comes to the covenant, knowing that the wizards are not well disposed to Magdalene. He has several useful books, all in Latin, written by Magdalene. These include five Tractati with Quality 11, two in Corpus, two in Animal, and one in Muto. He also has Lab Texts for The Beast Remade, Steed of Vengeance, Cheating the Reaper, The Eye of the Sage, Cloak of Black Feathers, and Curse of Circe. Finally he has the Lab Text for Dina’s Necklace. All the Lab Texts would need translation to be useful. He offers these books to the covenant in exchange for a necklace that will transform him into a woman, such as Magdalene had. The covenant’s course is not entirely clear. If the wizards had stolen Magdalene’s books that would clearly be a crime. Even if they commanded a servant to do so, they would be liable. But Menachem is not at all subject to Order Law. Is it worth taking him in and helping him to benefit from the books and irk an enemy? If Magdalene catches up to Menachem she will certainly kill him, or worse. Will the covenant stand by while a mundane is tormented by a fellow wizard?

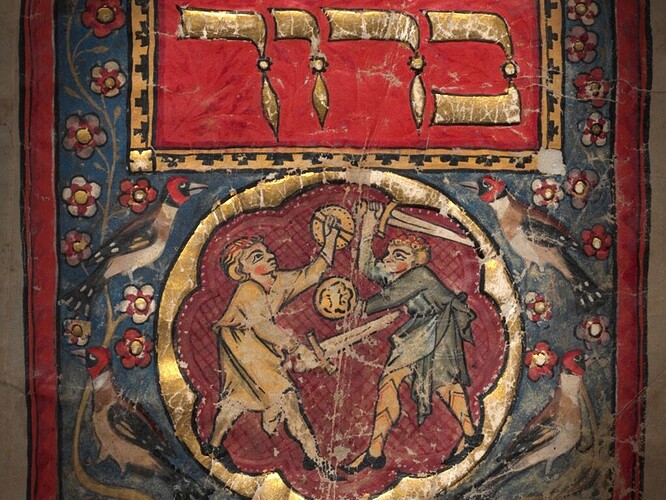

Dinah’s Necklace

A small gold necklace holding a garnet on a pendant. The device benefits from the shape and material bonus for jewelry to transform the self of +4. This is a lesser enchanted device with constant effect, for +4 levels), for a total level of 14. A Muto Corpus Lab Total of 28 was needed to create this enchanted device. A total of just 14 is needed to create it with the Lab Text.

Muto Corpus Level 10 - The Transformation of Adam to Eve

R: Touch, D: Sun, T: Ind

The target is transformed to be the opposite sex. Their primary and secondary sex characteristics change - a woman would grow a beard and have a penis, for instance. The target does not gain the ability to have children in their new state - that would violate the Limit of Essential Nature. Just like any constant magical effect, this device causes one point of warping a year if it is worn frequently.

(Base 3, +1 Touch, +2 Sun)

Menachem ben Qalonymus

Characteristics: Int +1, Per +1, Pre +1, Com +2, Str +1, Sta 0, Dex -1, Qik +1

Size: 0

Age: 25 (25)

Decrepitude: 0 (0)

Warping Score: 0 (1)

Confidence Score: 1 (3)

Virtues and Flaws

Free: Wanderer

Virtues: Educated (Hebrew), Well-Traveled, Linguist, Social Contacts (Merchants), Strong-Willed, Puissant Bargain

Flaws: Outsider (Major), Close Family Ties (Qalonymus Family), Driven (Minor), Pious (Minor)

Personality Traits: Driven to Become a Woman +3, Faithfully Jewish +3, Suspicious of magi +2, Quiet +2

Reputations: None.

Combat:

Dodging: Init +1, Atk n/a, Def -1, Dam n/a

Soak: 0 (Stamina)

Fatigue Levels: OK, 0, –1, –3, –5, Unconscious

Wound Penalties: –1 (1–5), –3 (6–10), –5 (11–15), Incapacitated (16–20)

Abilities:

Artes Liberales 1 (bookkeeping), Montpellier Lore 1 (Jews), City of Rome Lore 1 (Jews), Provence Lore 1 (Jews), Awareness 4 (night), Bargain 4+2 (shipping), Charm 3 (foreigners), Etiquette 3 (Jews), Folk Ken 3 (deals), Guile 3 (deals), Legerdemain 1 (books), Language: Ladino 2 (business), Language: Zarphatic 5 (poetry), Language: Occitan 4 (business), Language: Latin 3 (bargaining), Language: Arabic 4 (business), Language: Hebrew 3 (Torah), Language: Italian 2 (business), Language: Lingua Franca 2 (Western), Order of Hermes Lore 1 (Jerbiton), Stealth 3 (cities), Rabbinic Law 2 (business deals)

Equipment: Leger, pocket knife, stolen books.

Encumbrance: 0 (0)

Customization Notes: Menachem can take another four points of Virtues and Flaws. Menachem has not taken the Transvestite flaw, as he does not present as a member of a gender that does not match his physical sex. The Driven flaw is used to describe his desire to change his physical sex through magical means. Only when his physical sex is changed does he feel comfortable inhabiting a matching gender presentation. Note that our 2024 understanding of gender is very different from what someone in 1220 might have, but you can look to examples of gender queer people in the middle ages, such as the historical Qalonymus ben Qalonymus to guide your roleplaying.

Poem by Qalonymus ben Qalonymus

1322

Translated by Noam Sienna in A Rainbow Thread

What an awful fate for my mother,

that she bore a son. What a loss of all benefit!

Cursed be the one who announced to my father: "It’s a boy!"

Woe to him who has male sons.

Upon them a heavy yoke has been placed, restrictions and constraints,

some in private, some in public,

some to avoid the mere appearance of violation,

and some entering the most secret of places.

Strong statutes and awesome commandments,

six hundred and thirteen.

Who is the man who can do all that is written,

so that he might be spared?

Oh, but had the artisan who made me

created me instead—a fair woman.

Today I would be wise and insightful.

We would weave, my friends and I,

and in the moonlight spin our yarn,

and tell our stories to one another, from dusk till midnight.

We’d tell of the events of our day, silly things,

matters of no consequence.

But also I would grow very wise from the spinning,

and I would say, "Happy is she who knows how to work with combed

flax and weave it into fine white linen."

And at times, in the way of women,

I would lie down on the kitchen floor,

between the ovens, turn the coals, and taste the different dishes.

On holidays I would put on my best jewelry.

I would beat on the drum

and my clapping hands would ring.

And when I was ready and the time was right,

an excellent youth would be my fortune.

He would love me, place me on a pedestal.

Dress me in jewels of gold,

earrings, bracelets, necklaces.

And on the appointed day,

in the season of joy when brides are wed,

for seven days would the boy increase my delight and gladness.

Were I hungry, he would feed me with well-kneaded bread.

Were I thirsty, he would quench me with light and dark wine.

He would not chastise nor harshly treat me,

and my pleasure he would not diminish.

Every Sabbath, and each new moon,

his head would rest upon my breast.

The three husbandly duties he would fulfill,

rations, raiment, and regular intimacy.

And three wifely duties would I also fulfill,

[watching for menstrual] blood, [Sabbath candle] lights, and bread.

Father in heaven, who did miracles for our ancestors with fire and water,

You changed the fire of Chaldees so it would not burn hot,

You changed Dinah in the womb of her mother to a girl,

You changed the staff to a snake before a million eyes,

You changed [Moses’] hand to [leprous] white,

and the sea to dry land.

In the desert you turned rock to water,

hard flint to a fountain.

Who would then turn me from a man to woman?

Were I only to have merited this, being so graced by goodness.

What shall I say? Why cry or be bitter?

If my Father in heaven has decreed upon me

and has maimed me with an immutable deformity,

then I do not wish to remove it.

And the sorrow of the impossible

is a human pain that nothing will cure

and for which no comfort can be found.

So, I will bear and suffer

until I die and wither in the ground.

And since I have learned from our tradition

that we bless both the good and the bitter,

I will bless in a voice, hushed and weak,

Blessed are you, O Lord,

who has not made me a woman.